Introduction

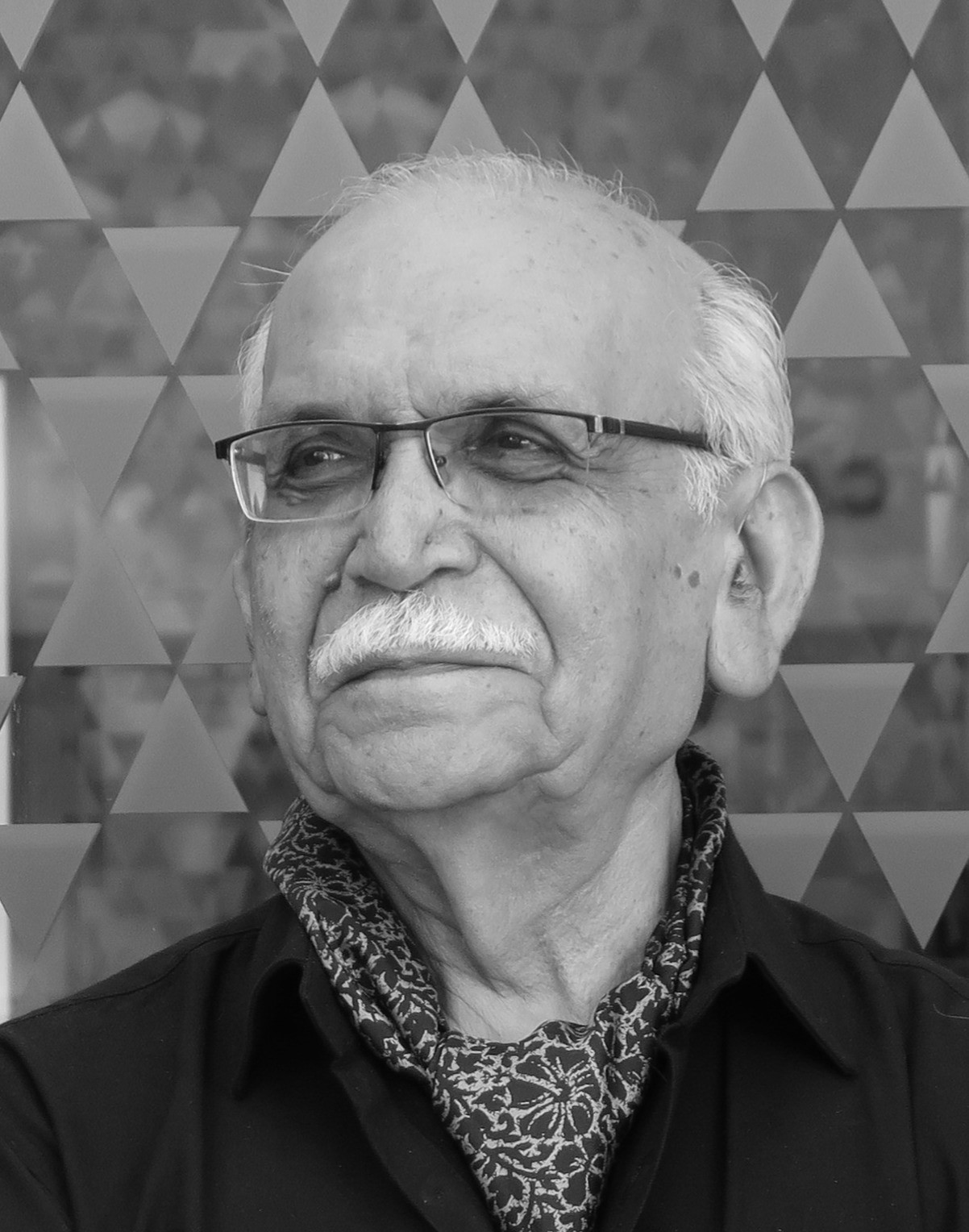

When Professor B. N. Goswamy passed away in November 2023, the art world lost one of its greatest historians. In July 2022, I had the privilege of speaking with him during the promotions of his book, ‘Conversations: India's Leading Art Historian Engages with 101 Themes, and More’ by Penguin Randomhouse. We met at the India International Centre in Delhi, where the then 88 year old art historian spoke with grace, clarity, and characteristic wit about devotional hymns, national anthems, management, and the role of teachers and lineages in Indian art—anchored by the opening line of the Hanuman Chalisa: Shri Guru Charan Saroj Raj, Nij Manu Mukur Sudhari—which likens the dust of the guru’s feet to a means of polishing one’s mind like a mirror. The conversation was never published at the time. But as we continue to reflect on Prof. Goswamy’s legacy, I’m grateful to the GBF Foundation for offering a space to share this.

Interview

This conversation was held at the India International Centre, Delhi on 27th July 2022 around the release of Dr Goswamy’s ‘Conversations: India's Leading Art Historian Engages with 101 Themes, and More’ by Penguin Randomhouse. Unfortunately, my phone was placed at a distance and Dr Goswamy was so soft-spoken that it was impossible to make out his voice on the recording. A filmmaker friend pitched in to increase the volume so that it could be transcribed, and it wasn’t lost. I had sent Dr Goswamy my questions by WhatsApp as I walked into the IIC, to prepare him for my questions and give him space to think. This wasn’t our first conversation. We met at least once a year since Dr Goswamy released a book once a year. That was one of the things that I wanted to ask him about. I had been told that he set the page and images first and then wrote the text for the page – much like in the Mughal karkhanas of old. He never answered that one. I met him first at the lecture for his book on Manaku in 2018. I had an interview set up with him the next day, so I was perhaps one of the very few in the audience who had read the book. In an audience of the foremost art historians in Delhi as well as journalists, I pressed him on his research into Manaku’s identity till he asked me after the lecture whether I had any questions left for the interview. Nevertheless, he was very courteous during the interview. Now in 2022, I walked into his room to find him washing his coffee cups so that the room was clean for our interview. His beloved wife had passed away since the last time I’d met him, and he looked frail. We made coffee and he came to sit down as the water boiled.

BNG: “Now what is this about Ram Singh Malam”.

RK: The first time that I interviewed you and sent the answers to you to look at, you sent back around six pages on Ram Singh Malam which I couldn’t use because there was a word limit to the article. But you’ve spoken about him in your book (Conversations) as well. Why is he so important?

BNG: I must have written about him in a column at least once. It's such an important story. A completely illiterate person is shipwrecked and stays for twelve years in Holland and other places. And wherever he goes, he picks up all kinds of skills – watchmaking, glass making, gunpowder, etc. And when he comes back to India, he just wanders around. Nobody employs him except this king in Kutch.

RK. So, he wasn't from Kutch?

BNG: He was from that area - Saurashtra. And this king picked him up and asked him to work for him. And he revolutionized Kutch so to speak. And look at his life. We don’t know what he was. Kutch had trade relationships with the east coast of Africa. It still does even today. So, he was shipwrecked in Amsterdam and then he made the Aina Mahal which is quite a wonderful thing. And there is no earlier records of most of these paintings in Kutch paintings. But my guess is, and I think it is as good a guess as anybody else's, that he was the one who brought these, and then he must have shown them to the Kutch ruler. And the ruler called his painters and asked if they could copy it. And there are five copies of each by local artists. But there are no names on these paintings. Someone used a rose as his symbol, someone else made a daffodil, and someone else a narcissus and you understand that the ‘Rose’ is better than the ‘Daffodil’.

The only school of landscape painting in India was in Kutch. When people saw these paintings and were told to copy them, they must have discussed it amongst themselves. How on earth is a Kutchi man sitting there – Kutch is not quite landbound, but it's certainly inland, interested in what is happening in Vienna, or the Pall Mall in London or something. They must have thought what nonsense this is. We know how to make perspective, let's look at this.

You know, have you heard of that great business guru in America? Who died a few years ago – CK Prahalad. He became a friend because of a lecture of mine. I was lecturing on Kutch, and he came along with some friends of mine and afterward, he was just completely floored, not by the lecture, but by the whole story of how this one man, in a certain sense, stirred so much up. And he said that is the essence of Indian entrepreneurship. He wrote that famous book called ‘The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid.’

This man CK was so esteemed by people in the highest echelons of government in America. President Bush would often send his private plane to fetch him from Michigan, where he was teaching, to come and advise him as an economist and business guru. So CK, with all that, said that this is what the essence of Indian innovation is. It's not only imitation. Of course, imitation is the basis of all progress. You won't be speaking the language you are speaking. I wouldn't be speaking the way I am. I wouldn't be walking the way I am had I not imitated my parents. Imitation is the beginning of it all. The Greeks had a word – mimesis. So, he said, there's nothing wrong with it.

Take art college students. They sit and make copies of Rodin etc. because they're learning to draw. This is the essence. A Zen master would say, ‘I've taught you this. Now forget all that I have taught you. Now do what you want.’ This is a very famous kind of Zen statement. And CK speaks in his book about the Tiffinwallahs in Bombay. And goes on for pages about how organized they are, what kind of service they provide, and how, if someone falls ill, somebody else automatically comes and fills in for them. This is one of the most organized institutions of its kind by people who are illiterate in the formal sense.

RK: Isn't art exactly that?

BNG: It can be. It's not necessarily that. It’s not enough that you keep copying self-consciously. You must learn by yourself after that. There’s a saying in German. I don’t remember the exact words. It’s common in academic terms - Kill your father. What does that mean? If you want to grow, go beyond what you’ve learned, don't limit yourself. It is a very startling thing for you and I who are taught to respect our elders, but it’s common there. The essence of innovation starts with imitation. Then it depends on how much creativity and strength you have.

If one reads the old Greek masters and Aristotle and so on, they emphasize this mimesis. Coomaraswamy wrote one of the most scintillating essays on the theory of art in Asia. The man had insights that we can only aspire to.

RK: So, I'll come back to those three, four questions that I had asked earlier, which, as I said, it feels a little wrong because you've moved on so much from there and I want to know what you're thinking now rather than what you were thinking at that point.

BNG: I won't say I've grown wiser. I've read a little more than I knew at that time. Actually. one grows with time. But quite consciously I think I have been broadening my repertoire; not repertoire - my scope. I feel very strongly that visually we are illiterate. I'm going to lecture in Bombay, part of the Centenary Celebrations of the Museum, and the title I've given to it is The Things That We Do Not See. That's the title of my lecture. The person who has made things has thought about it. We can’t be that person, but we can try to get under the skin of that person. Look at the amount of thinking that went behind iconography. Look at a statue of Vishnu – the chaturbujay, char baju, char hatha, with shank, chakra, gadha, hast. That's the most common. Now where did they come from? They aren’t just made up; they didn't come in a lottery. And there is a difference between iconography and iconology. Iconology is an understanding of icons. Iconography is the description that Vishnu has four arms, and he has four objects. That's an iconography. But why does he have them? Do they signify something higher, something deeper we hardly ever pay any attention to? And who asks those questions? And if you understand what the image says and why it came into someone’s mind.

It starts with Vishnu Vishnuh. The first Vishnu Sahasranam text. The first 2 words are Vishnu Vishnuh -Vishnu is the universe. Why is Vishnu blue or Krishna blue? Because the colour of the universe is blue. If you were to condense all space, which is much larger than the earth we live in, it would be blue. And when you think of it like that, since he is all-pervasive, you may not believe in him, but thinking from that point of view that he is all-pervasive, then the universe is concentrated in him. Then the objects are elements.

What are the elements – earth, water, air, fire, and ether? His consort is Bhudevi. She's standing between his legs. That is Earth. Where is water? Water is symbolized by the lotus. Fire is symbolized by the gadda that he carries. If you strike with a gadda, sparks will come out. Air – the chakra goes through the air and comes back, and the shanka is evolutive. It has space inside.

RK: Not because of the sound it makes.

BNG: Space. It's not like I'm saying something new or different. What I'm trying to say is that we don’t think. So, when you read something like this you don’t forget. Take the Hanuman Chalisa. I don’t know if you recite it or have memorized it. It starts with Shri Guru Saroj Raj. We recite it a million times but don’t think. The Lotus feet of the Guru from which you take the dust. Nij man mukudar sudhar. When mirrors used to be made of copper, you would clean them with the softest thing so that they wouldn’t get scratched. And the softest thing that Tulsidas can think of is the pollen taken from the lotus feet of my Guru. With that I cleanse – not clean, cleanse the mirror of my heart. Why do I need to do that? Baranau Raghuvar Bimal Yash. His aura is so clean because it has no additives. And if the mirror of my heart isn’t cleansed, then how can I see his glorious aura? It’s thrilling. We recite it like parrots. But if you pay some attention to all this, you will not forget this. You won't.

It's not that one is ignorant, but one is not concentrating enough on trying to understand what is being said. There’s a body called CCRT in Delhi. I used to lecture there. Teachers would come and stay for a month at a time. I would acquaint them with Indian culture. They were teachers of subjects like mathematics and geography, not arts or something. I would ask them if they knew the National Anthem. But this is not what you are here for.

RK: My questions are going to fall small in front of what you're saying. So, it doesn't matter. I'll ask the questions later. Don't worry about the interview.

BNG: I would ask them if they knew the National Anthem. You recite it every day in school. Why are Punjab, Sind, Gujarat, Maratha, Dravida, Utkal, Banga named? What is it? If this was a description of India, then where is Kashmir, Rajasthan, or Madhya Pradesh? It's not the rule of India. But if you look at the map of India, this is the outline of the map. After the complete Partition. The configuration starts from Punjab, Sindh, Gujarat, Maratha, Dravid, Odisha, and then Bengal. This is the configuration of India and an outline. I told the teachers that they will never forget the National Anthem and they agreed.

RK: Vindhya, Himachal?

BNG: It's not a geography lesson. But they must have thought of something. But we don’t see. It’s a consequence of the kind of superficial lives we lead. We float on the surface.

RK: Which brings me to an interesting question. How do you find your topics? How do you do people approach you? You write almost a book a year.

BNG: Not that much. Every two years or so.

RK: You're now on your 29th or 32nd book.

BNG: No. no. There are not so many. 25-26

RK: How do you find that level of interest?

BNG: There is one thing I'm convinced of. The day I stop reading and writing I decline both in the mind and the body. This is what keeps me afloat, so to speak. I'm 80, 88 years old. But look, all I'm saying is my mind is working so far. But books don't go into circulation. They don't sell. I'm not gaining anything out of these. At the end of this, what is that worth? Not for money. There's no money in this kind of work. But your question is the right question. What is the motivation? Nobody has ever asked me to write on a topic. I find something and then one thing leads to another.

RK: So how do you hunt down these topics?

BNG: if the idea appeals to me if I am drawn to an idea, person, period, or concept, then I don’t leave it. I sort of clench my teeth and get to it. You can call it being stubborn. I have decided and so I will do it. It’s a challenge to myself.

You see when I left the IAS, it was not an easy thing to do. I had no idea where I was going. I had no background in art, certainly not in art history. Who knows how life moves? It wasn’t that I had made up my mind that I’d do this or that. I thought, let's see what happens. My father was a judge. When I joined the IAS, it was a very small batch. 50-60 people from the whole of India. Right. So naturally it was prestigious. Even today, there’s a lot of social status and prestige attached to being an IAS officer. So, when I resigned, a friend of his went to my father and said, ‘Did he ask you?’ My father said ‘he didn’t ask me but if he was bright enough to get into the service, I'm sure he's using the same brightness to get out.’ I came on a scholarship of Rs 300. Of course, there have been sacrifices but all I’m saying is that your circumstances mould you.

In this book, ‘Conversations’ – these columns grew organically. I have written in the beginning that the editor of the Tribune came to me and asked me to write for them and I sat and thought. And when I had 100 topics, I agreed. There's no thread between one and the other even though you’ve found a thread of Ram Singh Malam. For example, I went to Bangalore and met Abhishek Poddar. Abhishek is very interested in photography, and he introduced me to the works of a photographer called Sebastian Salgado. Now I had heard the name Salgado, but I had never seen a picture by him. And I was so moved by this Brazilian photographer. So, I started researching this photographer because if I don’t know about him, very few people will know about him. So, it’s happenstance.

I ran into an article somewhere on the rivalry between Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolf Hurst in the 1880s and both bought cheap newspapers and turned them into sensationalist tabloids. With lies on lies. And I’ve just written this piece on fake news. And then when I started thinking about fake news, my mind went back to the Mahabharat - to Dronacharya and the battle at Kurukshetra. No one can defeat him, so Krishna tells Yudhistir to say what he said. In a way it was the truth and, in a way, a lie. A half-truth is what they called it.

RK: It was a lie.

BNG: It was done properly. In a loud voice, he said Ashwathama had died. In a lower voice – either the man or the elephant. And it was a lie. And nobody allowed him to forget this. In the end, he went to hell for this. So fake news isn’t new. It is very old. The difference is that the speed and the scale are becoming different. ‘Hillary Clinton has adopted an alien boy’ is the screaming headline in the National Enquirer. People will buy the paper to read it. Imagine a person in the Bible Belt and so on. He’ll believe it. Yes, it's interesting.

RK: You start the whole book by telling your readers that if they haven't read Coomaraswamy, you despair over them. Why?

BNG: (laughs) That was the first column regarding Ananda Coomaraswamy. I regard him as an iconic figure. The amount of knowledge Coomaraswamy had of culture, to date no one else had had. He was wrong on many counts about art history. But there was no one like him in his understanding of art history. As I said, when the editor asked me to write, I told him that I would reply to him the next day and I sat down to see how many columns I could write. I didn’t want to write a sporadic column. I wanted to write a standing column. I was surprised myself. I was ready with 100 themes in a matter of half an hour. Once I was confident, I then agreed.

RK: You reached 600. Now the count must be much more than 600.

BNG: 670. This was the 679th column that I wrote and filed last week. This is about one-fifth of my output.

RK: So, what brought about the book? Why now? Why did you wait for 600?

BNG: A lot of people would tell me that they cut out the columns and save them. Many people had files of the columns kept away.

RK: I have a Google alert for Dr. Goswamy, but I don't get the alerts for your column.

BNG: My wife was very keen. She said that you have subject matter. You should put them in a book. Coincidentally, because ‘Spirit of Indian Painting’ had done well. It was in it’s third edition. And just as I was debating in my mind if I should do an anthology or not, a letter came from Penguin (the publishers) saying that they wanted to do another book. So, the two things coalesced. I didn’t go to them. They came to me for a book. And this idea was running through my head and Karuna was still here and so (takes a pause and voice fades a bit) and I said I had this idea. See if it works for you. They asked me to send a sample. I sent 10-12 pages.

RK: But there is no logic to it.

BNG: No logic. There's no need for logic. There's no need for a thread in an essay. You should be able to read and enjoy it. Bakshe hai jalwa gul zauke tamasha e Ghalib. Chashm ko chahiye har rang mein wa ho jana. The radiance of a rose teaches you that its gift is that you should look around. It inspires you to look at more things. It teaches you to look at more things.

RK: That brings me to the question of who are the art historians that we should be reading.

BNG: That’s a difficult question. I read too little now.

RK: Really? The book moves from Desmond Lazaro to the lady who talked about Nathdwara paintings. Our youngsters barely know names like Khandalwala. I found one book by Archer in some library somewhere. A lot of these names have disappeared.

BNG: Like they have disappeared, my name would disappear. In 6-7 years, I will be gone as well. There’s no durability. Very few survive. Even Coomarasamy has disappeared. Ask your friends how many of them know of Coomaraswamy. His biography was published by Durai Raja Singam. 676 publications. Not books. Some are pamphlets, some introductions. Amazing, amazing man. When I started writing these columns, I wrote a tribute to Coomaraswamy. At the beginning, I used to give a tailpiece. To make it interesting so that people move out of their worlds and read more. What a writer that man was. He’s written an essay on Netramangala (the ceremony during which the painter gives life to the image of God. While his assistant holds a mirror, the painter turns his back to the statue and paints without looking directly at the statue's face). Can you imagine the man was a scientist? He didn't study art history for a single day. He was a geologist, and his mind was very organized. As a geologist, you must have a very sharp, analytical, and organized mind. He got into Tamilian and Sri Lankan culture, which led him to India. Roger Lipsey did an amazing job on his biography. He’s written 3 volumes on his work on Traditional Art and Symbolism and Metaphysics. Apart from that he wrote his thesis at the University of Pennsylvania. It is called Signature and Significance. It is different from his three volumes and it’s wonderful. I could write so much on Coomaraswamy. I just wanted people to have a little taste of a paragraph. I quote here, which I keep on quoting.

RK: Why don't museums bring together all these elements like dance, music – all the elements of Raas?

BNG: The most important thing in fieldwork. I ran behind the Pundo (pundits) for 3 years. Fieldwork tells you the essence of something. Sitting in a chair and theorizing won’t get you to the nitty gritty. Munshi Premchand has written somewhere that jis shaks ke lab me gokul ka lep ki Khushboo nahi basi hai, usko Hindustan pe likhne ka koi haq nahi hai. (The person who doesn’t remember the smell of Gokul’s (a popular religious site in Uttar Pradesh) earth’s, doesn’t have the right to write about Hindustan). Phenomenal. What observation!

About the Author

Ritika Kochhar is an author, artwriter, and curator with over two decades of experience in art, cultural communication, and public diplomacy. She is the founder of ArtRadio, a platform dedicated to storytelling, interviews, and public programming that explores the margins of South Asian art and heritage. Her writing has appeared in The Hindu, Frontline, India Today, and Art Asia Pacific and she has published three novels. Kochhar’s work often draws on mythology, ecology, and visual cultures to connect traditional narratives with contemporary concerns.

Instagram @dillikidiva

YouTube ritikakochhar-artradio

Academia Ritika Kochhar